Bells That Ring True

It's MY Chudstack and I get to talk about whatever I want

In this article, I will attempt to show why beginning from a position of universal doubt is not reasonable and should not be admitted at the beginning of any argument. The principle I propose to use in order to determine the reasonableness of any starting point is the observation of human action. In this process, I will show that Descartes’ doubt is insufficiently “universal" and that true doubt would lead one to agree with Heraclitus, Hume, or Protagoras. I will also demonstrate that the rational origin of any argument begins with a belief in God based on the principle of human action.

The Battleground

Whenever one begins to debate the existence of God with atheists, the believer enters into the atheist’s court where they must play by the atheist’s rules. It should be immediately obvious to anyone that quotes from the Bible are not likely to change the opinions of the atheist or the agnostic. The battleground, however, has not always been thusly fortified against our position. For the pre-moderns, the ball was in the believer’s court. Belief in the Christian God was the foundation of Western civilization. On account of this foundational bedrock, the medieval schoolman found that the fundamental principal of logic was that: “all knowledge rests on either authority or reason; but that whatever is deduced by reason depends ultimately on a premise derived from authority.”1 This understanding inherently gives weight to tradition, position, and most importantly, to God. The medieval, however, did not invent this principal. It was inherited from the Romans, who found the principal so weighty that they applied it to their theory of politics in Auctoritas et Potestas.

After many battles, this status quo seemed to have finally fallen to the scrutiny of Descartes. Descartes undermines the authority of God and inherited knowledge by beginning from a principal of so-called “universal doubt.” By starting with “nothing” Descartes draws inferences from immediate experiences. The dastardly regicide Descartes then crowns the individual consciousness as the crown-prince and arbiter of truth.2 Alas, the revolution was not complete, still extant was the medieval notion that “whatever is deduced by reason depends ultimately on a premise derived from authority.” All that Descartes managed to accomplish is to shift the authority to the Demos. Like Protagoras, Descartes seems to claim that man is the measure of all things. Now, each man could be his own arbiter of truth:

Good sense is, of all things among men, the most equally distributed; for every one thinks himself so abundantly provided with it, that those even who are the most difficult to satisfy in everything else, do not usually desire a larger measure of this quality than they already possess. And in this it is not likely that all are mistaken the conviction is rather to be held as testifying that the power of judging aright and of distinguishing truth from error, which is properly what is called good sense or reason, is by nature equal in all men[.]3

Insufficient Doubt

Skeptics (generally followers of Descartes) seem to have too much confidence in their “universal doubt.” They came to the battle armed with reason but did not doubt its existence (this task fell to other philosophers). Descartes seems to point all the way back to Plato’s dialogues wherein premises are accepted because they “have the ring of truth about them.” Socrates at least had some idea about what this sense of truth was: the soul recollecting its knowledge of the forms.4 Contrary to a radical doubt, Descartes places a nearly maniacal trust in this sense of truth. In disembodying reason, Descartes could not comprehend that the sense of truth might be subject to imperfection on account of sin. A truly radical doubt would have been capable of questioning reason itself. While later parties were able to more fully critique reason, it appears to me that the vast majority of moderns are either devotees of Descartes, or nihilists-by-default. I target Cartesians for this reason.

By stating the process of reasoning, C. S. Peirce makes perfectly clear why reason may be doubted: “That which determines us, from given premises, to draw one inference rather than another, is some habit of mind, whether it be constitutional or acquired.” In other words, some inferences ring true and some do not. Descartes does not have a sufficient answer for why the same bells that ring true for me, ring false for another. On account of what may we trust inferences? The medieval, in embodying the intellect in a concupiscent man subject to original sin, did away with this problem. If the same inferences ring true for one man and false for another, at least one man’s intellect is probably overshadowed by sin. Socrates recognized in the Republic that truth exists whether man perceives it or not and believed that truth is recollected from past lives. Those who have the wrong opinion have simply not remembered yet. By beginning with a truly radical doubt that questions reason itself, it is impossible to state why one inference should be trusted over another, or why any inference at all should be permitted.

Human Action as the Standard

Absolute doubt removes the man from his experiences, from his senses, even his sense of truth. However, no man actually lives out this philosophy. As the saying goes: “the only way to argue with a nihilist is to [threaten to] shoot him.” This points specifically at the fact that the beliefs of the nihilist are contradicted by the behavior of the nihilist. Peirce states: “The feeling of believing is a more or less sure indication of there being established in our nature some habit which will determine our actions.” The skeptic does not prepare himself for the day by doubting the existence of his underwear. No man predicates all of his behavior on doubt. “Doubt is an uneasy and dissatisfied state from which we struggle to free ourselves and pass into the state of belief.” As an economist would tell you, revealed preferences (behaviors) reveal the truth far better than stated preferences. No one truly behaves as a skeptic. If they did, they would appear to everyone as a madman. The standard for any starting principle should be that it reflects universal experience. This is what it means to enter into an argument in good faith. To step outside of lived reality is to step into the incomprehensible. If the nihilists are correct, it is reasonable to [redacted] oneself as soon as life becomes mildly uncomfortable, and yet, they usually don’t. To base the principles of a discussion on the stated preference of the skeptic, is to begin the discussion from a dishonest position. The skeptic’s behavior does not reflect their belief.

It appears clear to me that if one is to behave as if there is such a thing as truth, it is necessary to believe in God. Our behavior acts as evidence for the existence of God. The only other options are Heraclitus, Hume, or Protagoras. Heraclitus believed that all things were motion. If this were true, one could not be the same man from moment to moment, and the sense of self would be merely an illusion. This is clearly contradicted by human behavior, no one actually behaves like this:

Heraclitus’ “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man” found its brother in Hume’s problem of induction. According to Hume, there is no reason at all why the sun should not rise in the West tomorrow, or why a proton’s mass should not suddenly move from 1.67262192595(52)×10^-27th kilogram to one gram. The idea that something will continue to behave as it has, because it always has, it a logical fallacy. It is insufficient to state that it is thus because it is thus. Hume can be applauded for his consistency, but Hume would still be surprised if his clothes suddenly vanished.

Protagoras stated that “man is the measure of all things.” What appears true to one man and false to another is actually true for the first man and actually false for the second. “Just as each thing appears to me, so too it is for me, and just as it appears to you, so too again for you.”5 This too appears to be contradicted by human action. Humans attempt to convince each other of the truth, and as Peirce states: “Doubt is an uneasy and dissatisfied state from which we struggle to free ourselves and pass into the state of belief.” If one’s perception was the truth, we would never have any cause for doubt, and we could never be “mugged by reality.”

Human Action is Predicated on the Existence of God

Only on account of God can I step in the same river twice, only by God may I remain myself and the river itself, only on account of God does the mass of the proton not shift. This is not a God of the gaps fallacy. If there are rules to existence, something must be the ruler. From Heraclitus’ premise, the world appears as an ever-changing mass, formless and impossible to comprehend. From Hume’s belief, no action could be rational since the same behaviors will not necessarily produce the same results. From Protagoras’ perception, doubt would be an unnecessary sensation, and it would be unnecessary to ever change one’s mind. The believer, on the other hand, begins here:

And the earth was void and empty, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the spirit of God moved over the waters. And God said: Be light made. And light was made. And God saw the light that it was good; and he divided the light from the darkness.

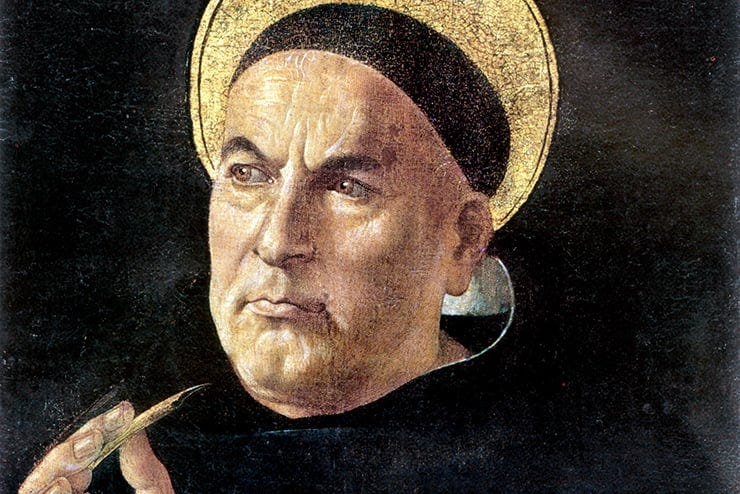

The world thus becomes comprehensible. Things can be defined, things can be fixed in place, belief in this allows one to act rationally. If all is flux, you cannot rightfully say: “I am myself” as all is relative. “I am myself” is as relative as “this box is heavy.” Heavy to whom? If one believes in God, light is separate from darkness, and one can remain oneself no matter how much they change. One may scoff at this aggressive claim, but when one reviews St. Thomas’ first proof for the existence of God, the reliance on an unmoved mover becomes clear. I do not seek here to argue from the position of absolute doubt. I seek to demonstrate that if one is to justify their revealed preferences (behavior), they will by necessity come upon the existence of God. I will quote here, as I am not nearly as intelligent as this Doctor of the Church.

Everything that is moved is moved by another. That some things are in motion—for example, the sun—is evident from sense. Therefore, it is moved by something else that moves it. This mover is itself either moved or not moved. If it is not, we have reached our conclusion—namely, that we must posit some unmoved mover. This we call God. If it is moved, it is moved by another mover. We must, consequently, either proceed to infinity, or we must arrive at some unmoved mover. Now, it is not possible to proceed to infinity. Hence, we must posit some prime unmoved mover.6

Proofs are required for two of these premises. First, that everything which is moved is moved by another; and second, “that in movers and things moved one cannot proceed to infinity.” That the reader may understand, I will also elaborate on what movement is for Aquinas (and Aristotle whom he references). Motion is any sort of change. The change is a motion from potentiality to actuality. A red ball has is potentially yellow, when it is painted yellow it moves from potentially yellow to actually yellow. The ball is now potentially red (or potentially any color).

First, we shall demonstrate that everything which is moved is by necessity moved by another. If something is capable of moving itself, it must contain within itself the principle of its own motion. Principles are the irreducible elements of being.7 This thing would be called the primary mover. If it does not contain the principle of its own motion, it is moved by another. This thing which causes motion within itself must move on account of itself, and not on account of only a part of itself, as this movement would be caused by only a part of itself (movement caused by another). The primary mover must either be wholly in motion or wholly at rest, for if one part was at rest while another moved, the whole could not be primarily moved. Nothing that is moved or is at rest on account of something else can be the primary mover. Therefore, everything that is moved must be moved by another.

Second, Aquinas will demonstrate that a procession to infinity is impossible:

In an ordered series of movers and things moved (this is a series in which one is moved by another according to an order), it is necessarily the fact that, when the first mover is removed or ceases to move, no other mover will move or be moved. For the first mover is the cause of motion for all the others. But, if there are movers and things moved following an order to infinity, there will be no first mover, but all would be as intermediate movers. Therefore, none of the others will be able to be moved, and thus nothing in the world will be moved.

I understand that this will be complex for many readers. I shall attempt to explain my point as clearly as possible. Without God, everything must be in constant motion, as Heraclitus states; or everything must be at rest, which is clearly impossible. If everything is motion, it is impossible for you to be the same man from second to second. No part of you remains the same. Therefore, you cannot be the same man from two seconds ago.

Neither is it possible that we are all at rest. As is said of Diogenes:

A student of philosophy, eager to display his powers of argument, approached Diogenes, introduced himself and said, “If it pleases you, sir, let me prove to you that there is no such thing as motion.” Whereupon Diogenes immediately got up and left.

As Aristotle and Plato make clear, the division of bodies is necessary to understand how a man can be the same man while also changing. From Plato’s Republic:

And suppose the objector [claiming that the same object can be both in motion and at rest in the same instant] to refine still further, and to draw the nice distinction that not only parts of tops, but whole tops, when they spin round with their pegs fixed on the spot, are at rest and in motion at the same time (and he may say the same of anything which revolves in the same spot), his objection would not be admitted by us, because in such cases things are not at rest and in motion in the same parts of themselves; we should rather say that they have both an axis and a circumference, and that the axis stands still, for there is no deviation from the perpendicular; and that the circumference goes round. But if, while revolving, the axis inclines either to the right or left, forwards or backwards, then in no point of view can they be at rest.8

When a man waves his hands while sitting down, his hands are in motion while his body is at rest. Only with this understanding is it possible to explain how we can change and yet remain the same person, and the answer to this problem of motion requires that God exists. I once was an Atheist, and now I am not. This was a movement of the intellect, the part of the intellect which believes. The part of the intellect (or soul) which perceives me as me, has remained. If I truly am the same man from moment to moment, then God must exist. Our action, if ration, is in and of itself predicated on a belief in God.

Reshaping The Battleground

Entertaining universal doubt is unnecessary. Our position is fortified by rational action; therefore, the position of the believer is the null hypothesis. The position of the Cartesians is not sufficiently doubtful to claim the accolade of universal doubt, as they irrationally trust in the sense of truth as their guiding light without any reason for doing so. However, to reject the sense of truth as a guiding principle leaves one to follow Heraclitus, Hume, or Protagoras. No one man guides his actions according to these philosophies, and to do so would appear as madness. In order for a man to justify his rational action and behavior, he will by necessity have to believe in God or act as if he believed in God.

On account of this belief in God, it is not necessary to trust in inferences on their own. It is more rational to trust the Word of God than logic rooted in a concupiscent body. “Not in bread alone doth man live, but in every word that proceeded from the mouth of God.”

Chance And Logic: The Fixation of Belief, C.S. Peirce

From the Proem of the above

Discourses, Descartes

Discussed most significantly in Plato’s Meno and Phaedo

Theaetetus 152a, Plato. I also must note that this is Plato writing “quoting” Socrates paraphrasing Protagoras. It is unclear what Protagoras actually believed since he was a sophist.

Contra Gentiles, Book 1, Chapter 13, St. Thomas Aquinas

Metaphysics 982a4-10

Republic, Book IV